The Old Bleach Linen Company

A Forgotten Irish Linen Mill in Randalstown

When I first started looking into the history of The Old Bleach Linen Company, I hadn’t fully appreciated just how far back its story reached, or how important it once was. Standing among the remains years later, it felt strange to think that this quiet, broken site began life around 1864 as a busy cotton mill, long before it became one of the names associated with Irish linen. Researching its past added a whole new layer to my visits — suddenly the ruins made more sense, and the scale of what had been lost became far clearer.

The mill’s transformation from cotton to linen came under the direction of Charles James Webb from Dublin. This change marked the most significant chapter in the site’s history. Linen production demanded both skill and precision, and Old Bleach clearly delivered. The fabric produced here wasn’t just for local or everyday use — it gained a reputation for exceptional quality, to the point that it was used to furnish royal palaces. That fact alone still surprises me, especially when I think about how anonymous and forgotten the site feels today.

As I dug deeper, I discovered that some of the designs produced at Old Bleach have survived long after the mill itself declined. Seeing that examples of its work are now preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum archive really brought home the importance of the place. It’s strange to imagine that patterns once created in these buildings now sit carefully catalogued and protected, while the site where they were made continues to fade away.

At its height, Old Bleach would have been a hive of activity. I try to picture it whenever I walk through the ruins — the constant motion of workers, the noise of machinery, the damp air heavy with steam and fibres. For generations, the mill wasn’t just an industrial site; it was a workplace, a livelihood, and a defining presence for the surrounding community. Families would have depended on it, schedules would have been shaped around its shifts, and its rhythms would have influenced everyday life in the area.

The decline, like so many industrial stories, seems quiet and gradual rather than dramatic. By the time the mill finally closed, possibly around 1980 with most of the buildings demolished in 1994, an era had already been slipping away for years. When I first visited in 2008, and again in 2010, that sense of loss was immediately obvious. Very little remained to show how the mill actually functioned. Most of the machinery was gone, floors had collapsed, and large sections of the buildings had been stripped back to shells. What was left felt fragile, as though it could disappear at any moment.

Walking through the site with my camera, I wasn’t just documenting decay — I felt like I was recording the final traces of something once hugely significant. There were moments where a wall opening or a surviving beam hinted at the scale of the operation, but for the most part, the workings of the mill had been erased. It took real effort to imagine the complexity and organisation that must once have existed where there was now only silence and rubble.

That’s why I’m always keen to hear from people who remember the mill as more than ruins. Anyone who worked there, or whose family was connected to it, holds a piece of the story that no amount of research can fully replace. Photographs from its working days would add life and context to what I’ve documented, bridging the gap between past and present. If anyone has images they’re willing to share, I’d be proud to include them here, with full credit, as part of a wider effort to keep the memory of Old Bleach alive.

For me, The Old Bleach Linen Company isn’t just another abandoned site. It represents the rise and fall of skilled industry, the quiet end of a place that once produced work of international importance, and the fragile nature of industrial heritage. Exploring its remains made me more aware of how quickly something vital can slip from common memory — unless we take the time to record it, share it, and tell its story while we still can.

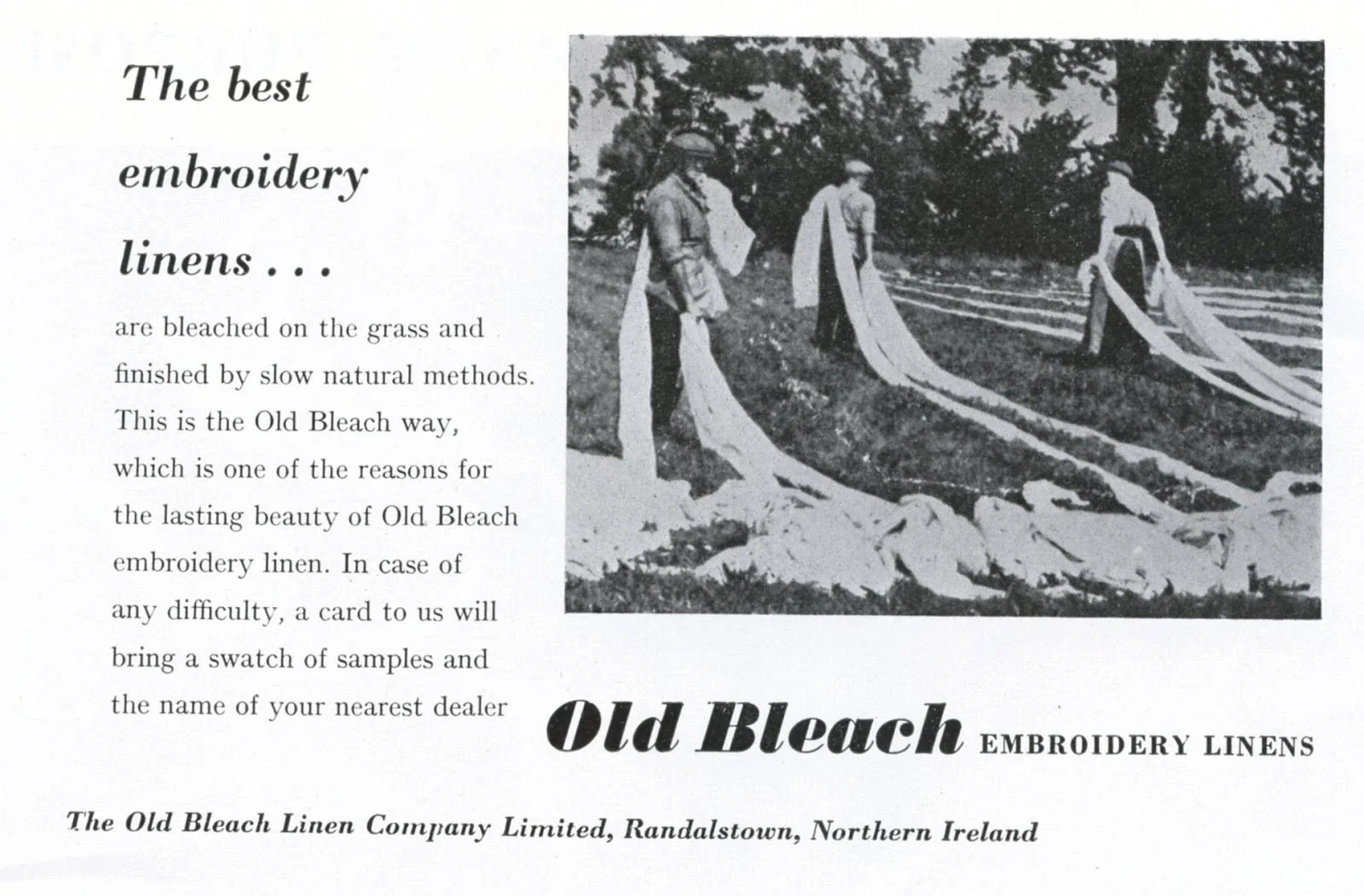

While researching the history of The Old Bleach Linen Company, I came across a fascinating old promotional postcard that clearly shows how respected their production methods once were. It highlights the traditional bleaching process the company became known for — long lengths of linen carefully spread out on open grass and slowly finished using natural methods. Referred to as “the Old Bleach way,” this careful approach helps explain why their embroidery linens earned such a strong reputation for lasting quality.

Imagery like this feels especially valuable now, given how little of the mill itself survives. The postcard shows workers handling vast stretches of fabric laid out across the fields, offering a rare visual insight into a key part of the process that helped put Old Bleach on the map. It reinforces just how much labour and craftsmanship went into textiles that later gained worldwide recognition, including use in royal residences and preservation in the V&A archive.

Finding this postcard adds another important layer to what remains of Old Bleach’s story — a small but meaningful connection to the everyday work that once took place on those grounds, long before the site fell silent. I’ve also found some additional images and postcards relating to Old Bleach Linen Company, which add more context to the company’s history and how it presented itself at the time.