St. Senan’s Hospital, Enniscorthy

Walking the Long Corridors of Memory

I first became aware of St. Senan’s Hospital the way most people in Enniscorthy do—not through history books, but through its presence. You can’t ignore it. Sitting high above the River Slaney, its red-brick walls and towers loom over the town, watching quietly as decades pass. For nearly 150 years, this building shaped lives, held stories, and reflected Ireland's understanding of mental health, care, and confinement.

I visited St. Senan’s myself on several occasions, at a time when it was slipping from use into silence. The first time was in 2014, when the hospital was still technically open, though parts of it already felt hollowed out. I returned again in 2015, just as closure was becoming inevitable. My final visit came in 2016, after the doors had shut for good—this time including a night visit, when the building felt most exposed, stripped of purpose and sound.

St. Senan’s opened in 1868, though it was then known as the Enniscorthy District Lunatic Asylum. The name alone places it firmly in the Victorian era, a time when mental illness was feared, misunderstood, and often hidden away. Designed by architects James Bell and James Barry Farrell, the hospital was built in an Italianate style—ornate, symmetrical, and imposing. It was meant to house around 70 patients. That number didn’t last long.

As I learned more about the hospital’s early years, it became clear that St. Senan’s quickly became overwhelmed. Families from across Wexford and beyond sent loved ones here when there were no other options. Poverty, trauma, epilepsy, alcoholism, post-natal depression—many conditions we now recognise and treat differently were once grounds for institutionalisation. By the early 20th century, the hospital held hundreds of patients, far beyond its original capacity.

During the First World War, numbers rose again. Men returned from the front carrying psychological wounds that had no name at the time. Shell shock, breakdowns, trauma—many ended up behind these walls. By 1915, more than 570 patients lived here, supported by a staff of around 350. The hospital had become a world unto itself.

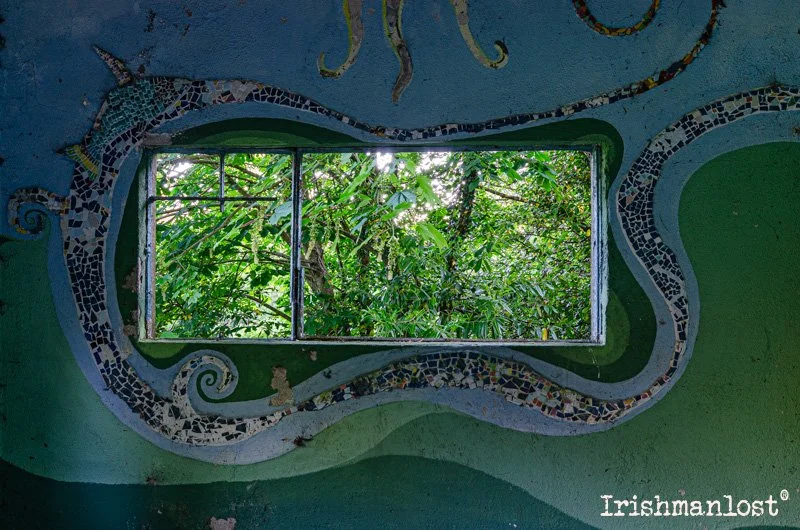

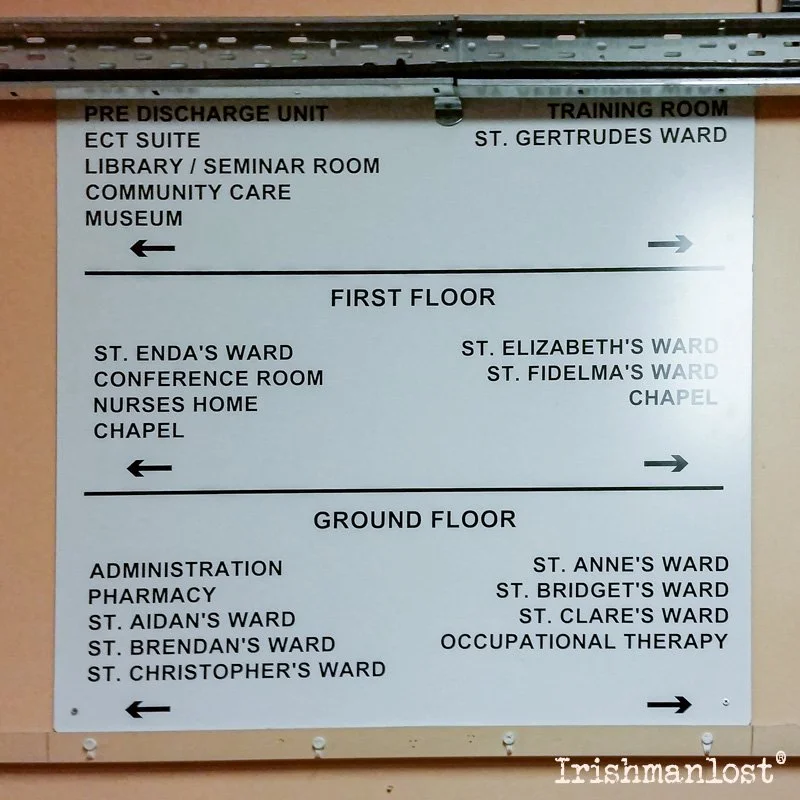

Walking the corridors years later, I could still sense that self-contained world. The hospital once had its own farm, workshops, church, power supply, and graveyard. Patients worked the land, baked bread, repaired clothes, and tended animals. For some, this routine offered structure and purpose. For others, it must have felt like a life suspended in time. By the time I was there, those routines had vanished, but the spaces built to contain them remained.

Language changed slowly. In the 1920s, it became the Enniscorthy Mental Hospital, shedding the word “asylum” but not entirely escaping its meaning. In the 1950s, it was renamed St. Senan’s Hospital, after the early Irish saint. The new name softened the edges, but the institution remained large, enclosed, and physically removed from the town below.

By the mid-20th century, St. Senan’s was one of the biggest employers in the area. Almost everyone in Enniscorthy knew someone who worked there—a nurse, a porter, a cleaner, a farmhand. For staff, the hospital was not just a workplace but a community. Many spent their entire careers within those walls. For patients, it was often a long-term home, sometimes lasting decades.

But ideas about mental health were changing. By the 1970s and 1980s, there was growing recognition that large psychiatric institutions could do as much harm as good. New policies emphasised care in the community, independence, dignity, and smaller, more humane environments. Slowly, patient numbers at St. Senan’s began to fall.

By the time of my visits, that decline was visible everywhere. Wards were empty. Paint peeled. Long corridors led nowhere. In daylight, the building felt abandoned but readable—its function still legible in signage, layouts, and architecture. At night, during my final visit in April 2016, it felt different entirely. Sound carried strangely. Darkness filled rooms that had once been constantly supervised. The scale of the place became overwhelming, and the absence of people felt heavier than their presence ever could have.

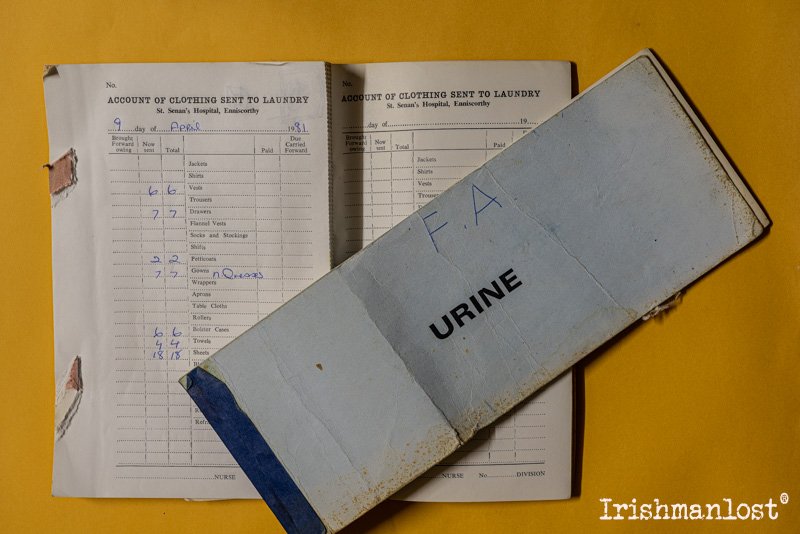

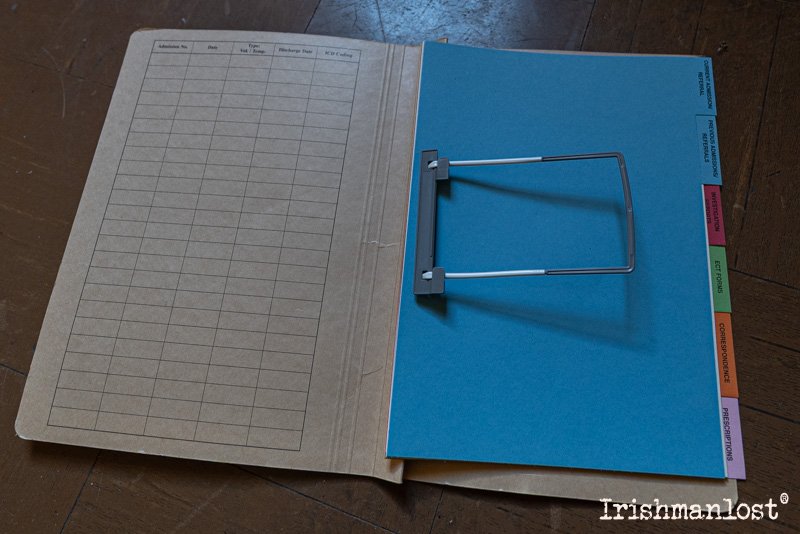

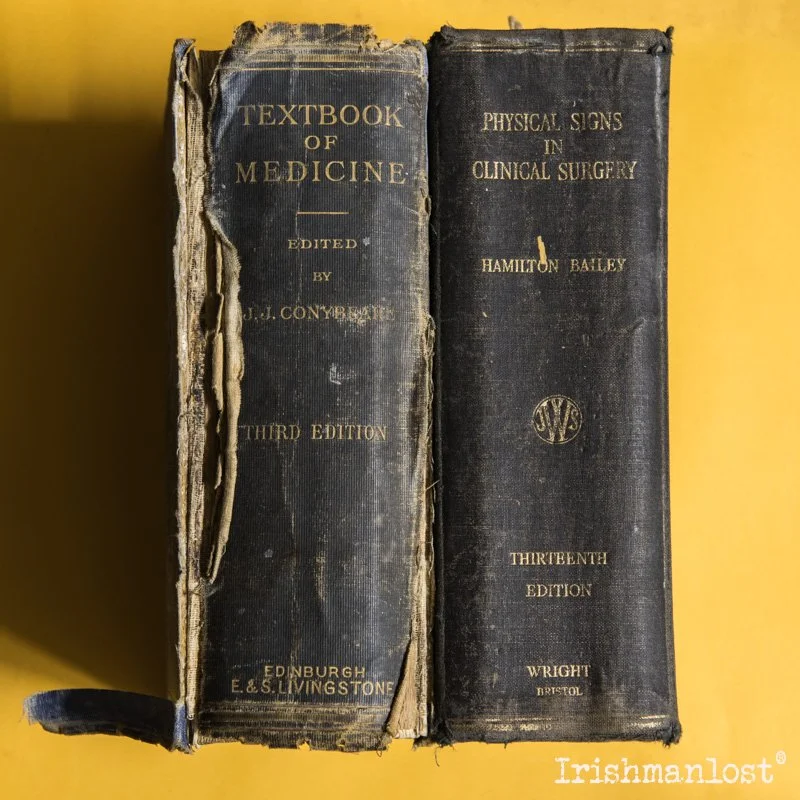

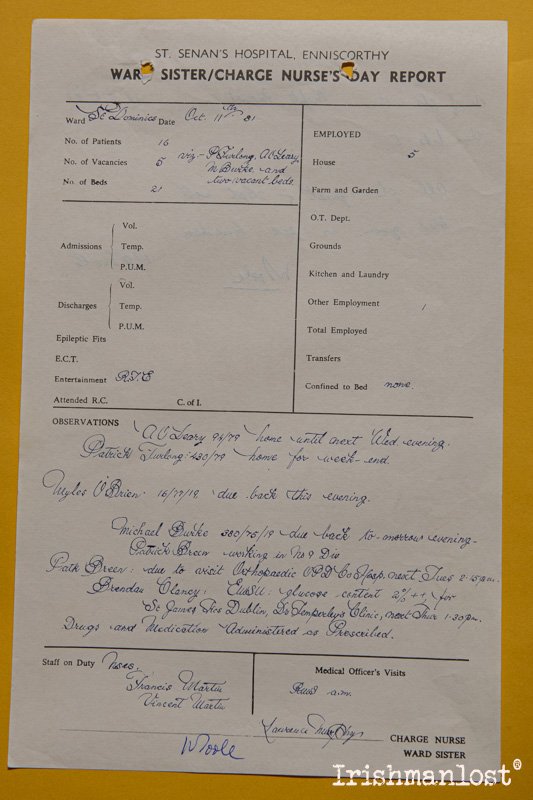

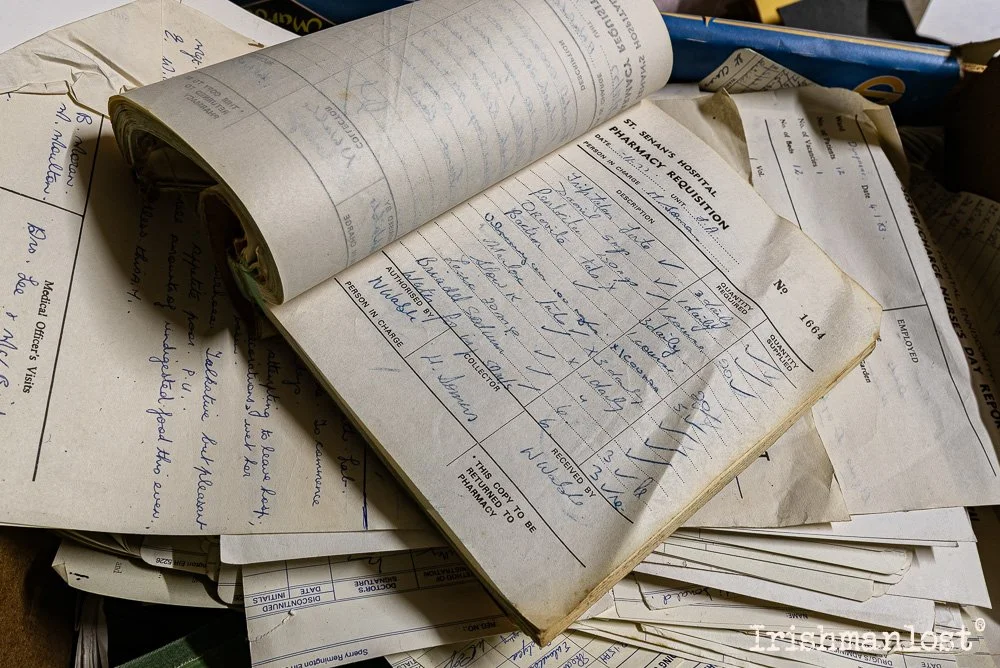

While exploring the quiet corridors of St. Senan’s, I came across a small collection of letters, observation sheets, and handwritten notes left scattered in drawers and offices, as if the day had stopped mid-sentence. The elegant but fading script captured the ordinary rhythm of life inside the asylum — names, duties, small daily details — fragile traces of a world that has long since fallen silent. You can view the full set of pages and read more here: Ink Left Behind.

In 2015, St. Senan’s Hospital officially closed its doors.

The closure marked the end of nearly a century and a half of continuous use. For some, it felt like progress—an overdue move away from institutional care. For others, it was deeply emotional. Staff who had dedicated their lives to the place watched it fall silent. Former patients lost a place that, for better or worse, had been their home.

Today, when I think back to those visits, I don’t just remember decay. I remember layers. Every corridor held echoes—footsteps, voices, routines repeated thousands of times. The nearby graveyard is perhaps the most haunting reminder. Many of those buried there have no marked graves, their names lost, their stories untold. Efforts to care for and remember the site feel essential, a way of acknowledging lives that were too easily forgotten.

What strikes me most is how St. Senan’s mirrors Ireland’s changing relationship with mental illness. It began as a symbol of care and control, evolved into a place of work and community, and ended as a reminder of how easily good intentions can harden into systems that outlive their usefulness. Its story is uncomfortable at times, but it matters.

St. Senan’s is not just a building. It is a record of how society once dealt with those who didn’t fit neatly into its expectations. As Enniscorthy looks toward the future, I hope the hospital’s past is neither erased nor romanticised, but understood. Whatever becomes of the building, the stories it holds deserve to be remembered—quietly, honestly, and with compassion.

The Site Today

As of 2025, St. Senan’s Hospital has entered a new chapter. The main Victorian building and sections of the surrounding grounds are being carefully redeveloped into residential apartments and housing. While its original function has long since ended, the structure remains part of Enniscorthy’s landscape—its past still present in the fabric of the place.